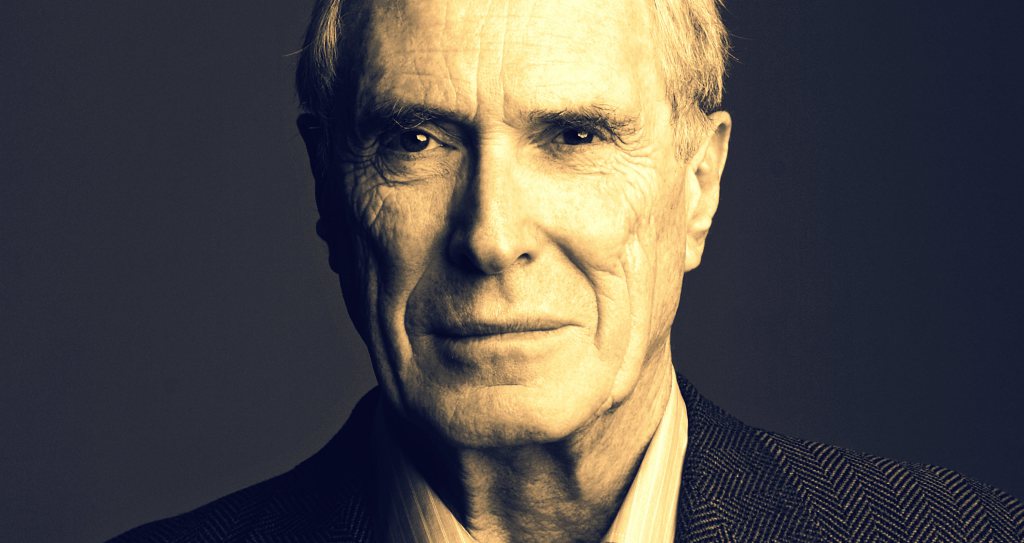

Eavan Boland

OUTSIDE HISTORY

There are outsiders, always. These stars –

these iron inklings of an Irish January,

whose light happened

thousands of years before

our pain did: they are, they have always been

outside history.

They keep their distance. Under them remains

a place where you found

you were human, and

a landscape in which you know you are mortal.

And a time to choose between them.

I have chosen:

out of myth into history I move to be

part of that ordeal

whose darkness is

only now reaching me from those fields,

those rivers, those roads clotted as

firmaments with the dead.

How slowly they die

as we kneel beside them, whisper in their ear.

And we are too late. We are always too late.

FUORI DALLA STORIA

Ci sono gli outsider, sempre. Queste stelle –

ferrei segnali di un gennaio irlandese,

la cui luce si formò

migliaia di anni prima

della nostra pena: sono, sono sempre state

fuori dalla storia.

Mantengono la distanza. Sotto di loro rimane

un luogo dove hai scoperto

di essere umana, e

un paesaggio dove sai di essere mortale.

E un momento di scegliere tra loro.

Io ho scelto:

fuori dal mito dentro la storia mi muovo per essere

parte di quel calvario

la cui oscurità

solo ora mi raggiunge da quei campi,

quei fiumi, quelle strade grumi di morti

come firmamenti.

Come muoiono lenti

mentre in ginocchio accanto a loro gli sussurriamo all’orecchio.

E arriviamo troppo tardi. Arriviamo sempre troppo tardi. Continua a leggere