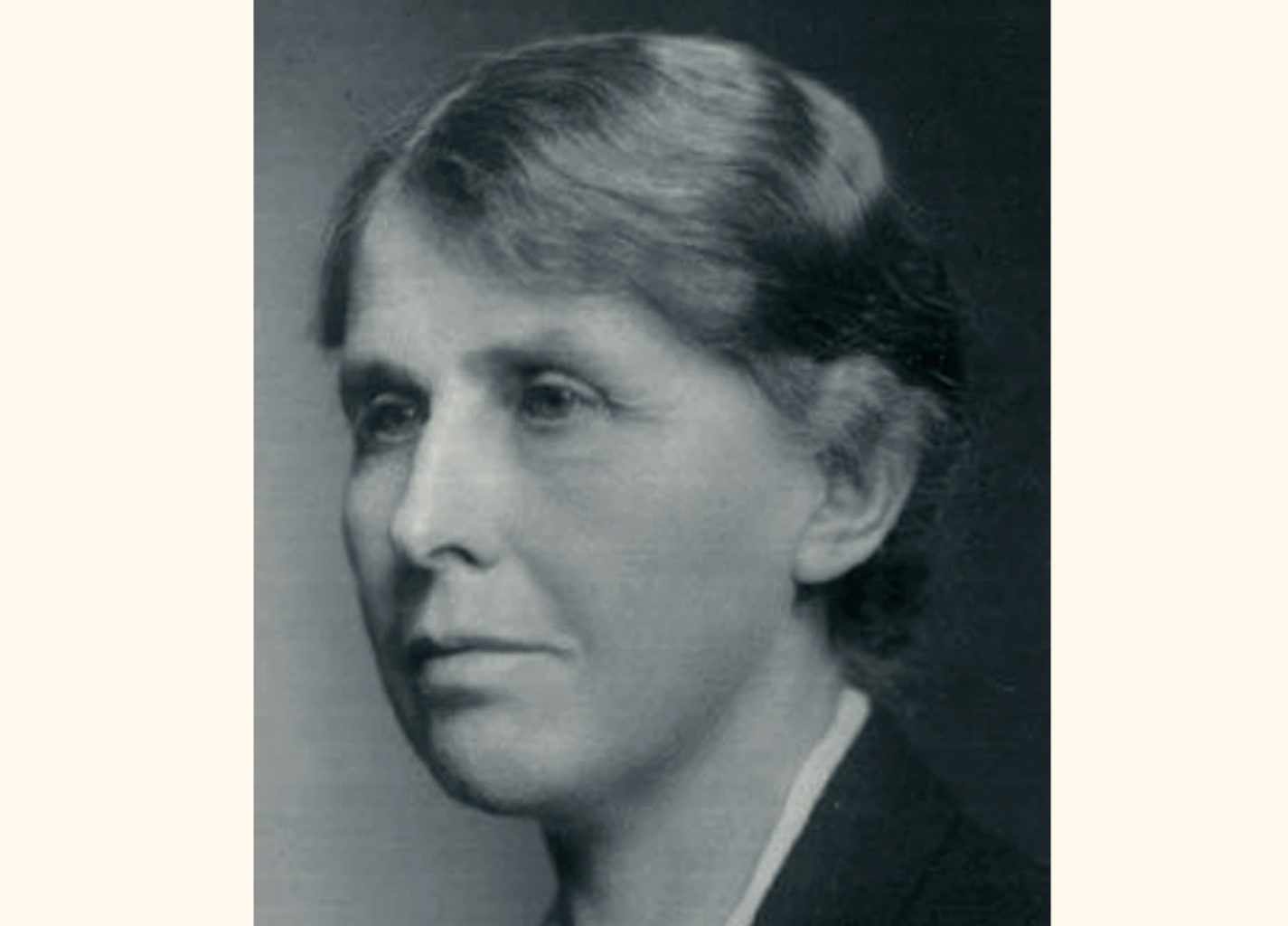

Hilda Doolittle

Pubblichiamo in Anteprima Editoriale tre poesie tratte dal volume H. D. Poesie Imagiste di Hilda Doolittle, a cura di Giorgia Sensi in uscita il 9 settembre 2021 con Interno Poesia.

NOTA DI GIORGIA SENSI

Nata nel 1886 a Bethlehem, Pennsylvania e conosciuta semplicemente con le iniziali H.D., la poeta Hilda Doolittle studiò letteratura greca al Bryn Mawr College di Philadelphia, ma si ritirò prima di aver completato gli studi. Nel 1907, per un solo anno, fu fidanzata con Ezra Pound. Le sue poesie, apparse su “Poetry” nel 1913, sono da Pound definite come un perfetto esempio di poetica imagista.

«Pound disse: “Ma Driade, questa è poesia.” Tirò un frego con la matita. “Taglia qui, abbrevia questo verso… “Hermes of the Ways” è un buon titolo. Questa la mando a Harriet Monroe di Poetry ...” E scrisse a grosse lettere “H.D. Imagiste” in fondo alla pagina».

Questa la versione che Hilda Doolittle, non ancora H. D., dà dell’incontro – lei quindicenne e lui sedicenne – con Ezra Pound.

L’incontro avvenne per la prima volta nel 1912 nella sala di lettura del British Museum e segnò la nascita del movimento poetico chiamato Imagismo.

Tra Ezra Pound e Hilda Doolittle nacque subito una stretta amicizia, un tormentato rapporto amoroso con numerose interruzioni, che durò per più di mezzo secolo, fino alla morte di Hilda, nel 1961.

H. D. e Ezra Pound fecero parte di quegli scrittori americani di inizio secolo, tra i quali T. S. Eliot, la cui vita e opera fu plasmata dalla scoperta dell’Europa, dove trascorsero la maggior parte della vita e scrissero le loro opere più importanti.

Ezra dominava Hilda (e non solo lei) affermandosi come sua guida e maestro, la avvicinava a nuovi libri e nuove idee, le dava occhi nuovi (come ebbe a dire più tardi), aiutandola e allo stesso tempo controllandola.

Apparentemente archiviato l’amore per Ezra Pound, la vita sentimentale di H. D. fu comunque tumultuosa. Nel 1913 sposò Richard Aldington, poeta inglese, che insieme a Hilda e Ezra frequentava la reading room e la celebre sala da tè del British Museum e che, con lei, partecipò alle prime antologie imagiste. Al di là della poesia, li accomunava un grande amore per i miti della Grecia classica.

Dopo la separazione da Aldington, H. D. iniziò una relazione con la scrittrice Frances Gregg, ebbe altre relazioni sia etero sia omosessuali, un rapporto di amicizia con D. H. Lawrence la cui natura non è mai stata chiarita, soffrì di disturbi nervosi, (il suo analista fu Sigmund Freud), ebbe crisi mistiche, mise al mondo una figlia, Perdita, avuta dal compositore Cecil Gray, e infine conobbe Bryher (il cui vero nome era Winifred Ellmann), una ricca industriale, che fu la sua compagna stabile per il resto della sua vita.

Poesie imagiste di H. D. (Hilda Doolittle)

Mid-day

The light beats upon me.

I am startled –

a split leaf crackles on the paved floor –

I am anguished – defeated.

A slight wind shakes the seed-pods –

my thoughts are spent

as the black seeds.

My thoughts tear me,

I dread their fever.

I am scattered in its whirl.

I am scattered like the hot shrivelled seeds.

The shrivelled seeds

are split on the path –

the grass bends with dust,

the grape slips under its crackled leaf:

yet far beyond the spent seed-pods,

and the blackened stalks of mint,

the poplar is bright on the hill,

the poplar spreads out, deep-rooted among trees.

O poplar, you are great

among the hill-stones,

while I perish on the path

among the crevices of the rocks. Continua a leggere